iOS Metaprogramming with Python, Pt 1

27 Jun 2015so meta

A metaprogram is a program that accepts other programs as input. In this post, we'll write a small python application that accepts your project's configuration plist as input, in order to change your application's behavior at runtime.

This is just one possible solution to a very common use case: pointing your app at different API environments.

movin' out

There comes a time in every configuration's life when it must grow up and make its way out of the source code of your application. For many iOS and OS X apps, a .plist file is a suitable place to store configuration info.

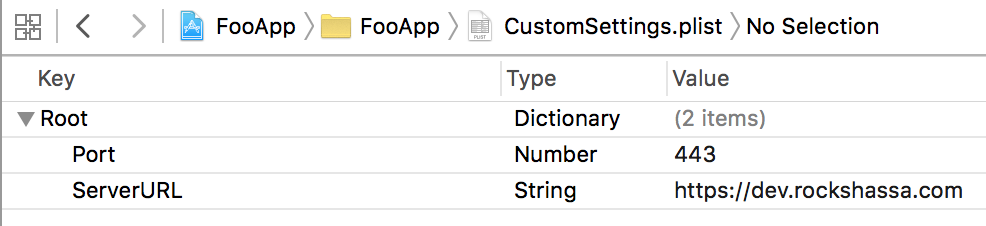

Inside Xcode, that .plist may look similar to this:

And the Swift code you use to access those values might look something like this:

let bundle = NSBundle.mainBundle()

if let path = bundle.pathForResource("CustomSettings", ofType: "plist") {

if let dict = NSDictionary(contentsOfFile: path) {

//note that serverURL and port are optional values

let serverURL = dict["ServerURL"]

let port = dict["Port"]

print(serverURL, port)

}

}Storing configuration info in the .plist is nice for a few reasons:

- Configuration changes are safer than code changes

- If we have multiple environments to point at, this gives us a single place handle that

- Abstracting out the configuration gives us a strong incentive to remove configuration-specific logic from the app

- .Plists are easy read and modify, in the event we want to automate the build of the app

don't just stand there, automate!

When deploying iOS applications for internal testing, we often need to build for several configurations. In this example, suppose we need to point at three different APIs, in this case named 'Dev', 'Staging', and 'Production'.

Let's assume that we're using Jenkins as our CI tool. We can build a python script that rewrites our .plist info, and invoke that script easily from Jenkins. We can specify our desired environment by passing it as a command line parameter. Our goal is to be able to set a new configuration simply by writing a bash command like:

$ python write_settings.py Productiongetting started

Create a file named write_settings.py and place it in the same folder that contains your configuration .plist. Now we can get started:

#intended for python 2.7

import os

import sys

import plistlib

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()First, we import the libraries we'll be using in this script. Then, we write an "ifmain", the purpose of which is explained nicely here on Stack Overflow.

That if statement will be evaluated as True when the script is invoked directly via command line. At that point, we immediately invoke main(). Let's implement that next:

def main():

#grab our command line parameter

environment = sys.argv.pop()

path = 'CustomSettings.plist'

#read the config into memory

plist = plistlib.readPlist(path)

#edit the configuration

editPlist(plist, environment)

#delete the old copy of the .plist

os.remove(path)

#write our new one in its place

plistlib.writePlist(plist, path)This code is fairly straightforward, except that we haven't implemented editPlist(plist,environment) yet. Lets do that next:

def editPlist(plist, env):

fmt = 'https://{}.rockshassa.com'

if env == 'Dev':

server = fmt.format('dev')

port = 443

elif env == 'Staging':

server = fmt.format('staging')

port = 9001

elif env == 'Production':

server = fmt.format('prod')

port = 123

else:

exit('invalid environment specified: ' + env)

for key in plist:

if key == 'ServerURL':

plist[key] = server

elif key == 'Port':

plist[key] = portThis performs the edit of the plist according to the environment parameter we provided when invoking the script. If we passed in an unrecognized parameter (or no parameter), the script will abort, providing an explanation why.

putting it all together

A full gist of the python script, with more verbose logging is available here. The additional logging is useful when viewing console logs from Jenkins. Now, all we need to do is invoke this script before running our xcodebuild command.

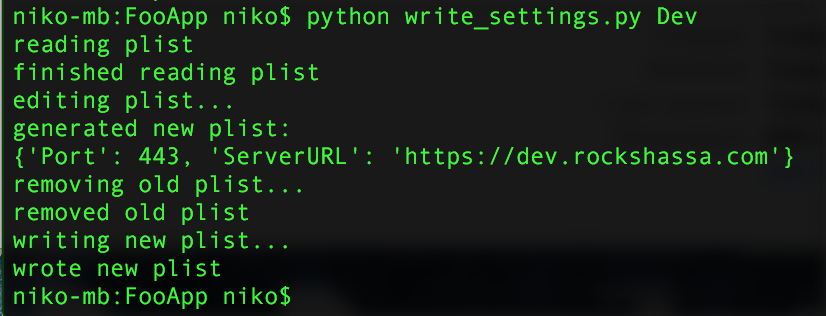

The invocation and subsequent output of the gist script should look like so:

And thats it!

This example is is a simple one, but method behind it can scale to handle other kinds of configuration information too. I've used it successfully to impement configs for feature toggles, URLs, ports, branding information, API keys, and even request headers.

After some practice, I hope you'll find that abstracting out configuration data in this way leads to more flexible, maintainable, and testable applications.

full gist